-

Las exportaciones andaluzas logran un récord histórico en los dos primeros meses del año, con 7.009 millones y un alza del 9,2% interanual

Las exportaciones de Andalucía lograron un nuevo registro histórico entre enero y febrero de 2024, al alcanzar los 7.009 millones de euros, la mayor cifra contabilizada para los dos primeros meses de un año desde que existen datos homologables (1995), gracias a un incremento interanual de las ventas del 9,2%. Con este incremento, que contrasta…

-

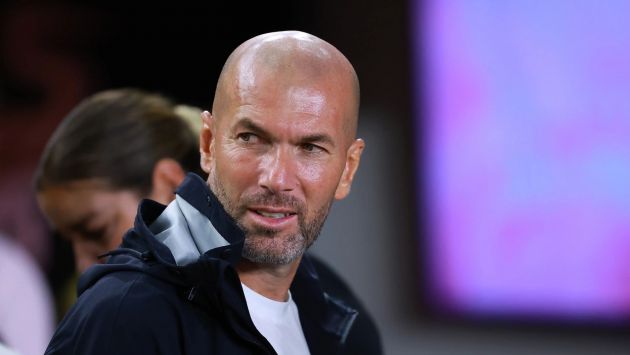

La leyenda del Real Madrid, Zinedine Zidane, está a un paso de volver a la dirección

Icono del Real Madrid y Francia Zinedine Zidane se acerca a su primer puesto como entrenador desde que dejó Los Blancos en 2021. Zidane solo ha dirigido al Real Madrid y al Castilla, pero se dice que está cerca de una nueva experiencia más allá de las fronteras de España, Francia e Italia, donde lo…

-

Planuri culturale pentru weekend – Știri din Madrid

Noaptea cărților 2024 stă vineri După succesul primei ediții, revine ciclul „Teatru și drepturile omului”. Fanii lecturii vor putea discuta cu Espido Freire la Serrería Belga Astăzi, vineri, în ajunul weekendului, se sărbătorește cea de-a 19-a ediție a La Noche de Los Libros. Un program organizat de Comunitatea Madrid la care participă Consiliul Local prin…

-

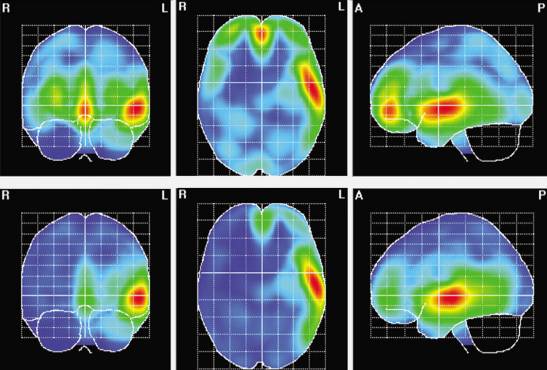

Creierul bărbaților și femeilor răspunde diferit la un film violent – Știință Știri

The filme Au capacitatea de a ne declanșa emoțiile și de a ne afecta, dar impactul nu este același în rândul tuturor telespectatorilor și, potrivit unui nou studiu, nici între femei și bărbați. Cercetătorii de la universitățile Complutense (UCM) și Carlos III din Madrid, împreună cu cea din Oviedo, au folosit electroencefalograma pentru a înregistra…

-

Războiul civil și perspectiva unică a fotojurnalismului de război – Știri din Spania

Război civil Probabil că nu este filmul la care te aștepți, dar este mult mai mult decât îți imaginezi. A24 a lansat în sfârșit acest film care a devenit unul dintre cele mai așteptate ale anului, în mare parte datorită protagonistului său, Kirsten Dunst. Dacă nu știți despre ce este vorba, ne duce la a…

-

BojGlobal scoate la sorți un grătar cu grătar – cadouri și mostre gratuite – Știri de agrement

BoxwoodGlobal tombolă pe contul său de Instagram un grătar cu grătar, cu grătar detașabil. Vremea bună se bucură făcând grătare pe terasă și întâlniri cu prietenii. Gratarul gratar are o placa detasabila si canelata, realizata cu un strat antiaderent usor de curatat. De asemenea, vine cu un capac de sticlă detașabil care vă permite să…

-

Secretele ascunse ale unei cetăți vechi: Povestea unui tunel misterios

Secretele ascunse ale unei cetăți vechi: Povestea unui tunel misterios În ținuturile noastre se află o cetate veche, în alb și negru, care pare să fi fost uitată de timp. Străjuită de munți și vegheată de pădurea înverzită ce-i dăruiește umbra sa, cetatea pare să păstreze în adâncurile sale multe secrete nedescoperite. Una dintre aceste…

-

Pinarello Dogma XC 2024 elimina 2 especificaciones de carbono para MTB de suspensión total y cola dura

El lanzamiento de estas 2 nuevas bicicletas de montaña Pinarello Dogma XC ha sido objeto de burlas durante más tiempo del que tomó desarrollarlas. Y esa es quizás la parte más loca de la historia de cómo un relativamente recién llegado a la escena de las bicicletas de montaña produjo dos bicicletas de XC ganadoras…

-

¡Los MC del viernes de “Voice Actor and Night Play 2024” serán Tomokazu Seki y Fairuz Ai! Publicación del “libro de perfiles” escrito a mano de dos personas♪

¡Los MC del viernes de “Voice Actor and Night Play 2024” serán Tomokazu Seki y Fairuz Ai! Publicación del “libro de perfiles” escrito a mano de dos personas♪ Contenido original en Inglés

-

#3 112 – Semana de la IA: VASA-1

#3 112 – Semana de la IA: VASA-1 19 de abril de 2024 por Craig Shames El último avance en IA llega de la mano de Microsoft y permite resucitar a los muertos. Especie de. Gracias a VASA-1, ahora es posible dar vida a una imagen sencilla y dotarla de sonido sincronizado. Permitir que cuadros…